Replacing the manaka

Garífuna Language

Intensely studied since the early 20th century by linguists who specialize in native Caribbean and South American languages, Garífuna is an Arawak language with many vocabulary words and affixes from the Carib language. Arawak and Carib are just two of the various indigenous languages of South America. Groups of native peoples broke away from their tribes in South America and spread out over almost all of the Caribbean islands. European settlers started to arrive at the turn of the 1500s and in time, Africans were brought in to work the lands as slaves, replacing the Indians who had all but died out from disease and hard labor. By the middle of the 17th century, a large group of Africans had formed on St. Vincent Island (where Indians still managed to survive), arriving at different times throughout history. Through living among the native Indians of St. Vincent (Arawak speakers), the Africans completely acquired their language and culture. The Arawak language is still spoken in some parts of South America, including Colombia, Venezuela, Suriname and the Guyanas.

French colonists also lived among the native peoples and Garínagu on St. Vincent up until the latter’s departure at the end of the 1700s. In fact, by that time, most of the Garínagu had taken French names and were bilingual in French; bilingualism is one of the chief mechanisms in which foreign words are exchanged from one language to another. For this reason, many basic words in Garífuna (days of the week, most numbers, etc.) demonstrate a strong French influence. Moreover, speech communities have a way of “nativizing” words (pronouncing a foreign word not as it is in its source language but rather according to the phonological rules within one’s own language). In speaking Arawak and French, as well as any individual Spanish and English words, the earliest Garínagu applied their own native African pronunciation, creating a very African-sounding language. Through time, other foreign words that entered the language since the 16th century have also changed with Garífuna pronunciation, sounding less like the original European source word and more “Garífuna”.

Introduction

Why aren’t there more African words in the Garífuna language?

Contrary to its melodic tone reminiscent of African speech, Garífuna is not an African language. To date, there are less than five attested African loan words in the Garífuna language. When two languages come into contact, they will normally accept foreign words into each other’s language – if – the speakers of both languages acknowledge an equal social prestige between both groups. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Garínagu learned French and accepted French words into their language because they admired the French people with whom they cohabited, even giving them the best parts of their land on St. Vincent. It is not known (although it is highly probable) if French speakers on St. Vincent accepted Garífuna words into their language as well.

However, when two groups come together and there are no loan words in one of the languages, it is normally because the group without the loan words consider themselves the dominant group or it could be that they are more numerous. In the case of the Garífuna, there is evidence to suggest that the Kalípona (the Arawak descent group of the Lesser Antilles, also known as ‘Island Carib’) forced the Africans to learn their language and customs. If it were just the case of the dominant group (the Kalípona) being more numerous, then we would expect the non-dominant group (the Africans) to retain some of their language; in the very least a handful of terminology specific to their culture.

The fact that there is little to no African vocabulary in Garífuna and that no creole formed (a language with some vestiges of African structure based on European vocabulary, normally created by large communities of Blacks in the early stages of Caribbean settlement), shows us that the Indians must have been in control – in power and in number (by the mid 1600s, the French and British acknowledged the islands of St. Vincent and Dominica as Kalípona territories). This social structure prevented Africans from forming an Indo-African creole. The Africans simply acquired the indigenous vernacular immediately as a second language and Indian domination would have prevented the Africans from speaking their mother tongues.

Is it true that Garífuna is 45% Arawak, 25% Carib, 15% French and the rest is Spanish and/or English?

This may have been true at one time during the early 1600s, but it is certainly no longer true today. There are a few things to consider:

1) This formula referred to the vocabulary of the language, not the entire structure

2) This formula was based on the vocabulary of the indigenous peoples of the island of Dominica

One of the first linguists to analyze Garífuna language was Claudius De Goeje in the early and mid 1900s. De Goeje, a specialist in northern South American languages, argues that (as of 1946) 28% of Garífuna vocabulary was Carib; the structure was Arawak with hardly a trace of Carib syntactical influence.

Then in 1961, Douglas Taylor, a specialist in linguistics of the native Caribbean peoples, said that just 22% of Garífuna vocabulary had Carib words – less than 20 years later! In a later analysis, Taylor says that only a few Carib vocabulary words are left and even these words are showing a remarkable decline in use. As the practice of speaking with mostly Carib vocabulary words fell from prestige (it was especially esteemed before the 16th century, with trade between the Island and the South American native peoples), speakers would have replaced these words with Arawak items. Even today in Livingston, many Garífuna young men do not consider that they use “Arawak” or “Carib” words, but most are conscious that there are sometimes two ways to say the same word. However, those men who are aware of the difference in languages and who are passionate about the survival of the Carib element in Garífuna language, make it a point to use the Carib version whenever possible.

It’s been almost 65 years since that first calculation and as yet, no one has completed another morphological study that reflects the changes that Garífuna has experienced. If I had to supply an educated guess, I would say that the calculation is now:

70% Arawak, 5% Carib, 15% French and 10% Spanish and/or English.

With this formula, why isn’t Garífuna considered a mixed language?

Figuratively speaking, every language is a mixed language. English has elements of German, French, Hindu, Japanese – the list goes on – yet English is not commonly referred to as a ‘mixed language’. To date, no language has been discovered that developed in isolation, that is, a language that has had no contact with another language group whatsoever. Even in the most remote regions, a cultural group that does not have regular contact with the dominant culture will at the very least have contact with another remote tribe. As cultures come into contact and new ideas and concepts are exchanged, so do words for these new ideas become exchanged between languages. If you refer to Garífuna a mixed language because it has elements of many languages, then for you, every language a mixed language.

Literally speaking, a mixed language has a specific definition. It is one that is created when speakers of no more than two speech communities come together and deliberately create a third language based on elements of the two languages. Speakers of this group often do not identify with either group; a third language was created to separate themselves from the groups and create a brand new culture. Structurally, mixed languages normally have a clean divide, for example, all nouns from one language and all verbs from the second language. This was certainly not the case in the creation of the Kalípona language; Kalípona Indians on Dominica proudly pledged their allegiance to their Carib allies in the South American mainland.

Like all Native American languages, Garífuna is decidedly complex and not a language that one can just “pick up”.

Stages of Garífuna language development

I have designated four stages of Garífuna language evolution, based on linguistic as well as cultural and political events. Click in the box for further information about each stage.

Like all Native American languages, Garífuna is decidedly complex and not a language that one can just “pick up”.

Español

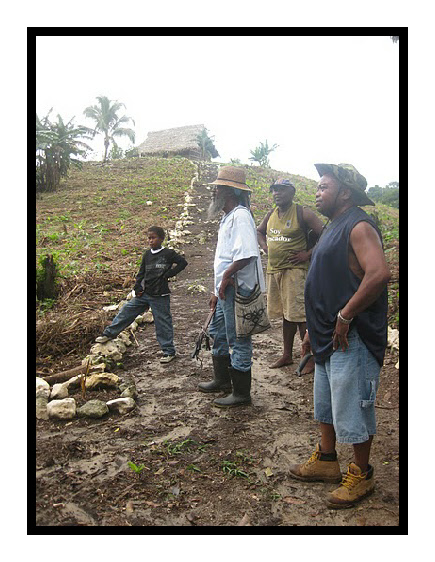

Gangadiwali (property), Livingston, Guatemala, November 2010

Tomás, Basillo, Fermin,

Román

Photo courtesy of Román Ávila Zuñiga

Gangadiwali, November 2010

Photos courtesy of Román Ávila Zuñiga